Historical Research

(2002 - 2016)

NOTE: Work-in-progress. Please check back as more material is added once permissions have been granted from various institutions.

This section includes related research and ephemera of historical significance that directly informed the making of the project Through Darkness to Light: Photographs Along the Underground Railroad, such as: facsimiles of newspaper ads, society minutes, academic papers, in addition to quotes and accounts from participants in the Underground Railroad. Where available, images from the various collections used to piece together the route are shown. As well as, information that explains specific locations, stops, and/or people all organized according to the documented route. Overarching ephemera is presented at the beginning of this page. Below is where ephemera specific to the route is shown. The epigraphs add Underground Railroad participants’ voices to the journey and include well-known figures as well as local people.

The Underground Railroad operated in opposition to the law. The first Fugitive Slave Law was passed in 1793 providing for the return of enslaved blacks who had escaped and crossed state boundaries. A second stronger law was passed as part of the Missouri Compromise in 1850.

Map of Underground Railroad routes from 1830 - 1865. Compiled from The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom by Wilbur H. Siebert, 1898.

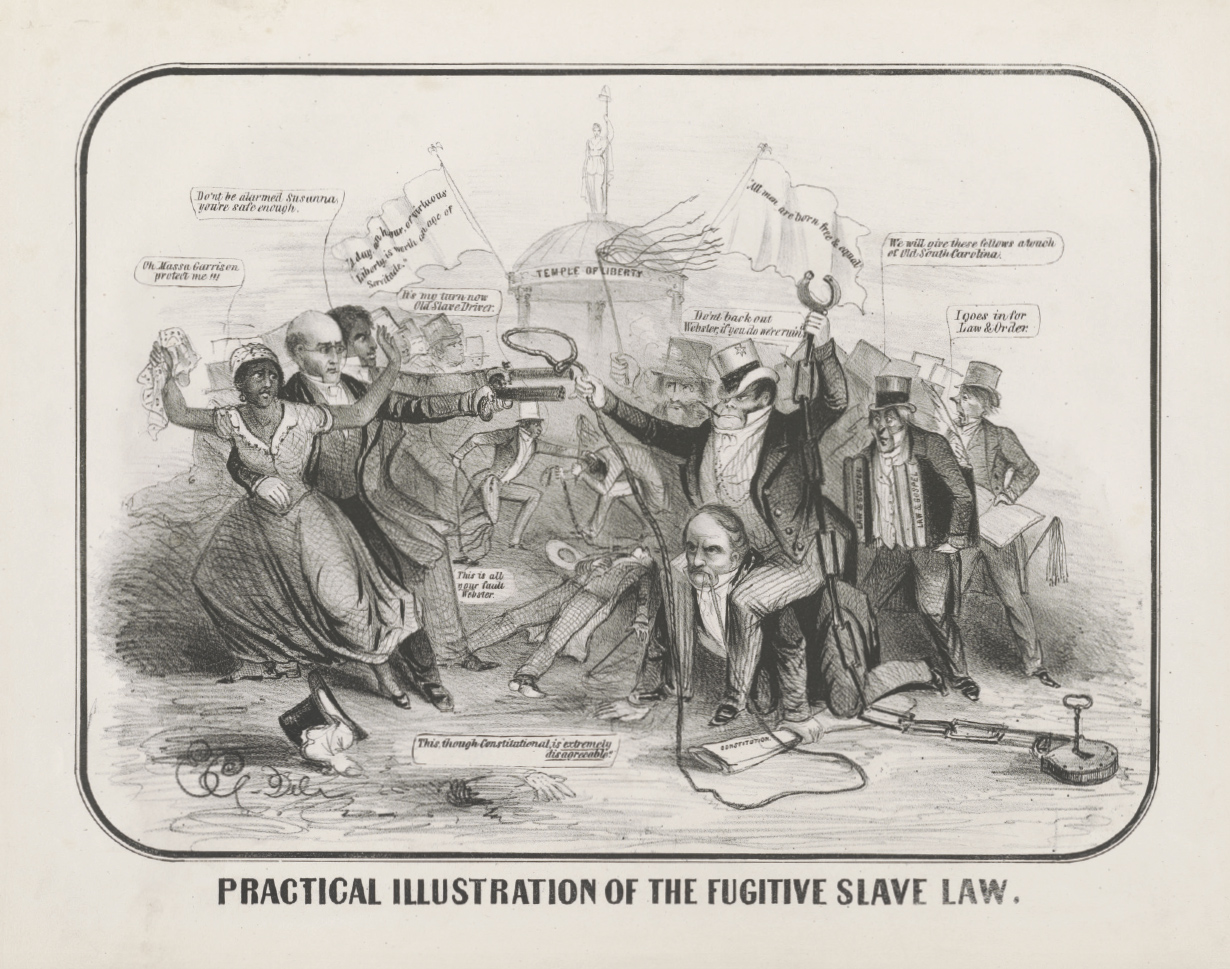

Practical Illustration of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1851, a satirical cartoon capturing the hostility between Northern abolitionists, portrayed on the left, and supporters of the Fugitive Slave Act, on the right, including Secretary of State Daniel Webster, who bears a slave catcher on his back. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Front of Signed Underground Railroad Pledge. Indiana Historical Society, M0199

Back of Signed Underground Railroad Pledge has a code and the signature of J. Pearce. Indiana Historical Society, M0199

Frederick Douglass stated that he could “think no better exposure of slavery can be made than is made by the laws of the states in which slavery exists.”

“If more than seven slaves together are found in any road without a white person, twenty lashes a piece; for visiting a plantation without a written pass, ten lashes; for letting loose a boat from where it is made fast, thirty-nine lashes for the first offense; and for the second, shall have cut off from his head one ear; for keeping or carrying a club, thirty-nine lashes; for having any article for sale, without a ticket from his master, ten lashes; for traveling in any other than the most usual and accustomed road, when going alone to any place, forty lashes; for traveling in the night without a pass, forty lashes.’ He further states, “I am afraid you do not understand the awful character of these lashes. You must bring it before your mind. A human being in a perfect state of nudity, tied hand and foot to a stake, and a strong man standing behind with a heavy whip, knotted at the end, each blow cutting into the flesh, and leaving the warm blood dripping to the feet, and for these trifles.” ‘For being found in another person’s negro-quarters, forty lashes; for hunting with dogs in the woods, thirty lashes; for being on horseback without the written permission of his master, twenty-five lashes; for riding or going abroad in the night, or riding horses in the day time, without leave, a slave may be whipped, cropped, or branded in the cheek with the letter R, or otherwise punished, such punishment not extending to life, or so as to render him unfit for labor.”

[top] Manifest of a slave ship sailing from Richmond, Virginia, to New Orleans, October 18, 1840. African American Resource Center, New Orleans Public Library.

[bottom]

Enslaved workers picking cotton in South Carolina, c. 1860. Rob Oechsle Collection.

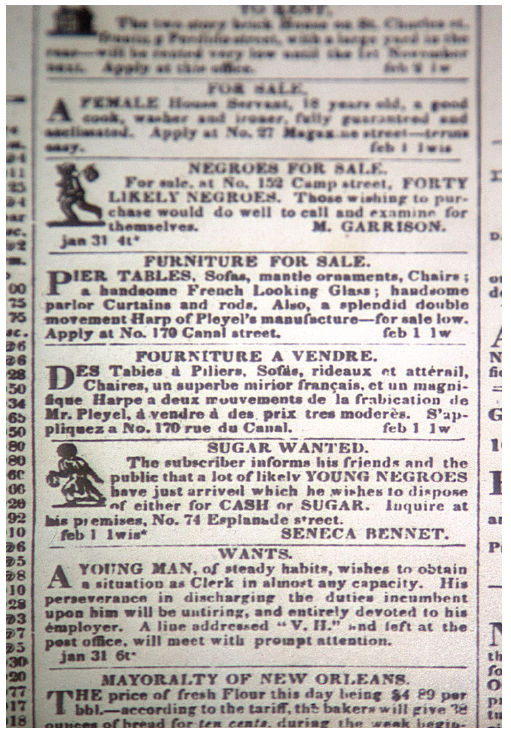

Advertisement offering enslaved people in exchange for cash or sugar in The Daily Picayune, February 4, 1840. Louisiana Division/City Archives, New Orleans Public Library.

Advertisement announcing “Negroes for Sale” and listing their trades in The Daily Picayune, February 5, 1840. Louisiana Division/City Archives, New Orleans Public Library.

1,400 mile documented route from the project Through Darkness to Light. It covers seven states from Louisiana to Michigan and then on into Canada. A journey that would have taken roughly three months to complete.

“No man can tell the intense agony which was felt by the slave, when wavering on the point of making his escape. All that he has is at stake; and even that which he has not, is at stake, also. The life which he has, may be lost, and the liberty which he seeks, may not be granted.”

Decision to Leave.

Magnolia Plantation on the Cane River, Louisiana, 2013

The land on which Magnolia Plantation stands was originally acquired by Jean Baptiste LeComte I in 1753. At the height of their prosperity in 1860, the family produced more cotton than anyone else in the Natchitoches Parish. During its prime, it is likely that at least 75 people lived at Magnolia. All of the slave cabins at Magnolia were placed in rows, creating a structured village atmosphere. As with many other plantations in the area, Magnolia’s slave cabins were turned into sharecropper cabins after Emancipation.

Magnolia Plantation survey, 1850s. Courtesy of the LeComte/Hertzog family and the Cane River National Heritage Area.

Historic American Buildings Survey, C., Cizek, E. D. & Tulane University, S. O. A. (1933) Magnolia Plantation, Slave Quarters, LA Route 119, Natchitoches, Natchitoches Parish, LA. Louisiana Natchitoches Natchitoches Parish, 1933. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Tin type of the cotton gin invented by Eli Whitney in 1793, Magnolia Plantation, 2014, Jeanine Michna-Bales. The yield of raw cotton doubled each decade after 1800. Thereby fueling the growth of slavery. While it was true that the cotton gin reduced the labor of removing seeds, it did not reduce the need for slaves to grow and pick the cotton. Cotton growing became so profitable for the planters that it greatly increased their demand for both land and slave labor. In 1790 there were six slave states; in 1860 there were 15.

Advertisements offering rewards for the recapture of runaway enslaved workers in the New Orleans Bee, November 16, 1833. Louisiana Division/City Archives, New Orleans Public Library.

“After dark I drove to the place agreed upon to meet in a piece of woods one mile from the town of Wirt. I had been at the appointed place but a very short time when Mr. DeBaptiste sang out, “Here is $10,000 from Hunter’s Bottom tonight.” A good Negro at that time would fetch from $1,000 up. We loaded them in...and started with the cargo of human charges towards the North Star.”

Other Underground Railroad communities possessed such moral authority that the network became a defining characteristic of the area. Such was the case with the Central and Eastern routes that ran through Indiana. The Neil’s Creek Anti-slavery Society, of Jefferson County, had quite a few members that were notable stationmasters, including the Reverend Thomas Hicklin and John H. Tibbets, who wrote of his experiences with the Underground Railroad in his reminiscences. The area included a large African American community of free and enslaved blacks called Africa, morally strong whites who adamantly believed that all people were created equal, a school dedicated to educating people of any color, as well as various religious organizations.

Dr. Samuel Tibbets was a cofounder and trustee of the Eleutherian College in Lancaster, Indiana, which was one of the earliest educational opportunities for women and African-Americans before the Civil War. He was an abolitionist and president of Neil's Creek Anti-Slavery Society, 1839-1845. His son, John Henry Tibbets, was an Underground Railroad conductor. John's document, The Reminiscences of Slavery Times, is a rare first-hand account of his adventures. The Tibbets family brought their underground railroad methods from Clermont County, Ohio, where they cofounded the abolitionist Lindale Baptist Church.

On the Way to the Hicklin House Station.

San Jacinto, Indiana, 2013

William and Margaret Hicklin acquired 320 acres in Jennings County Indiana on Little Graham Creek in 1819. Their sons Thomas Hicklin, Lewis Hicklin, John L. Hicklin and James Hicklin lived on this land and operated an outstanding Underground Railroad Station. Lewis and Thomas Hicklin became ministers and John and Martha Hicklin were members of Graham Baptist Church and in 1842 donated two acres of land for the church. James Hicklin was dismissed, from this church for "breaking the law and aiding to convey slaves from their masters". Lewis Hicklin was an agent for the Anti-Slavery Society and started Neil's Creek Anti-Slavery Society of Lancaster, Indiana, and many others. The Hicklin Station was located just ten miles north of Eleutherian College in Lancaster, Indiana. There are documented stories in the William Seibert Papers about the Hicklin Station and their work in moving freedom seekers north to freedom. Wright Rea, the slave catcher of Madison, Indiana, watched the Hicklin Station very closely to try to catch the family in their Railroad activities, but was never successful in that effort. William, wife Margaret and son Thomas Hicklin are buried at Home site, the rest of the family moved to Oregon in 1849.

Thomas Hicklin, an active abolitionist in Jennings County, operated a station one half mile east of San Jacinto and enslaved blacks to another station on Otter Creek in Campbell Township, and to a station at the home of John Vawter. Instead of continuing on, some fugitives remained in a black settlement southwest of Vernon. ["A Glimpse of Pioneer Life in Jennings County," 137, Alice Ann Bundy Collection, Indiana Division, Indiana State Library; Coffin, Reminiscences, 181-82.]

“Wright Ray, a noted negro catcher... was also sheriff of Jefferson County for many years and used his office for that purpose. [He] was known all over Kentucky and was always applied to when a slave got away.”

Elias Conwell House.

Along Old Michigan Road, a major north-south artery between Kentucky and Michigan, Napoleon, Indiana, 2013

The Michigan Road ran from Madison to northern Indiana and, once there, the fugitives may have taken the Chicago to Detroit trace to either Illinois or Michigan. Following the Michigan Road from Madison to South Bend or Michigan City, the fugitives and conductors could also have veered off to La Porte, the "door" to the prairie, or to the northeast and Detroit.

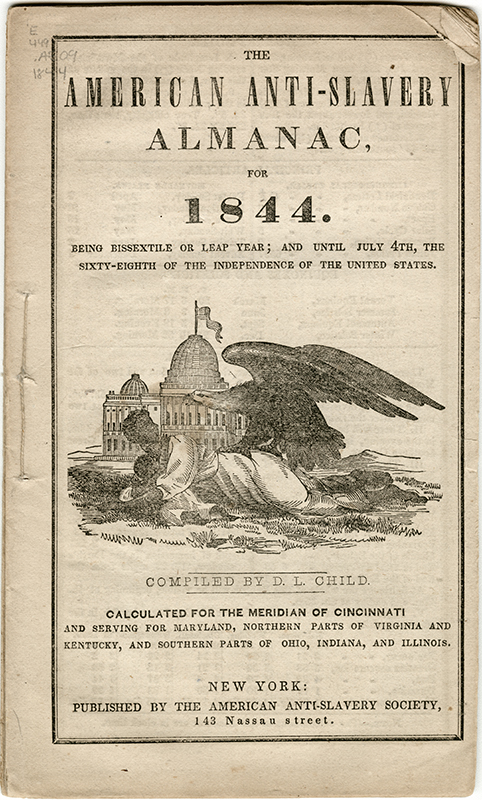

Cover of the American Anti-Slavery Almanac, 1844. Indiana Historical Society.

A Brief Respite.

Abolitionist William Beard’s house, Union County, Indiana, 2014

Also from Madison, Indiana, enslaved blacks could travel to Brooksburg, Marble Hill, or Vevay, but the next main stop was in Union County at the home of abolitionist William Beard, of Salem in Union County. Beard was just as active as Levi Coffin in Newport. Members of the Henry County Female Anti-Slavery Society took up donations to buy 127 yards of free-labor cotton in order to sew garments: vests, coats, pants, dresses, shirts, and socks. Two-thirds of the garments were directed to Salem, Union County, care of William Beard. Apparently Beard forwarded many of the reputed 2,000 enslaved blacks Coffin is said to have sent to Canada. From Union County the self-emancipated slaves might go to various points in Decatur, Dearborn, Rush, Henry, and Wayne counties. [Henry County Female Anti-Slavery Society minutes, Indiana Division, Indiana State Library.]

A Safe Place to Regroup.

House of Levi Coffin, who was unofficially dubbed the president of the Underground Railroad, Fountain City (formerly Newport), Indiana, 2014

The Underground Railroad was a loosely organized network whose participants had no titles, but friends and supporters of Levi Coffin—who, with his wife, Catherine, was an important organizer and abolitionist over four decades—referred to him as “president.” And their home became known as "The Grand Central Station of the Underground Railroad."

“The dictates of humanity came in opposition to the law of the land, and we ignored the law.”

Many of the Quakers of Indiana came from North Carolina and Tennessee and witnessed first-hand the atrocities of slavery. Including Levi Coffin and other members of his family who settled in and around Newport (now Fountain City), Indiana. They formed an Anti-Slavery Society and were regular contributors to the newspaper The Free Labor Advocate which championed immediate emancipation of all slaves, as well as only purchasing goods and produce that did not involve slave labor. Levi and Catharine Coffin were adamant supporters of the Underground Railroad while in Indiana and continued to support it after their move to Cincinnati, Ohio. The Levi Coffin Home is a National Historic Landmark and is now a part of the Levi Coffin Indiana State Museum Historic Site.

Levi and Catharine Coffin were Quakers from North Carolina who opposed slavery and became very active with the Underground Railroad in Indiana. During the 20 years they lived in Newport, they worked to provide transportation, shelter, food and clothing for hundreds of freedom seekers. Many of their stories are told in Levi Coffin’s 1876 memoir, Reminiscences.

Their eight-room house was the third home of Levi and Catharine Coffin in Newport, and it was a safe haven for hundreds of enslaved blacks on their journey to Canada. Levi and Catharine Coffin’s home became known as “The Grand Central Station of the Underground Railroad.” The Coffins and others who worked on this special “railroad” were defying federal laws of the time.

From the outside it looks like a normal, beautifully-restored, Federal-style brick home built in 1839. Being a Quaker home, the Coffin house would not have had many of the era’s decorative features such as narrow columns, delicate beading or dentil trim. On the inside, however, it has some unusual features that served an important purpose in American history. Most rooms in the home have at least two ways out, there is a spring-fed well in the basement for easy access to water, plenty of room upstairs allowed for extra visitors, and large attic and storage garrets on the side of the rear room made for convenient hiding places. The location of the house, on Highway 27 at the center of an abolitionist Quaker community, allowed the entire community to act as lookouts for the Coffins and give them plenty of warning when bounty hunters came into town.

For their journey north, freedom seekers often used three main routes to cross from slavery to freedom — through Madison or Jeffersonville in Indiana, or Cincinnati, OH. From these points, slaves traveled to Newport through the Underground Railroad. The Coffins’ “station” was so successful that every enslaved person who passed through eventually reached freedom.

Cover of The Free Labor Advocate and Anti-Slavery Chronicle, 1842. Friends Collection, Lilly Library, Earlham College.

Advertisement for Levi Coffin’s store promising “free labor dry goods and groceries” in the Free Labor Advocate, and Anti-Slavery Chronicle, July 1, 1847. Friends Collection, Lilly Library, Earlham College.

Advertisement outlining the aims of the North Star, an anti-slavery weekly proposed by Frederick Douglass, in the Free Labor Advocate, and Anti-Slavery Chronicle, September 30, 1847. Friends Collection, Lilly Library, Earlham College.

Approaching the Seminary.

Near Spartanburg, Indiana, 2014

“Differences in government, discipline, and privileges will not be made with regard to color, rank, or wealth.”

Union Literary Institute was one of the first schools to offer higher education without regard to color or sex before the Civil War. It was established in 1846 by a biracial board, including free blacks from nearby settlements. At the time, Indiana laws did not allow blacks to attend the public schools. Students labored four hours a day in exchange for room and board.

The school was supported by local and national donations, including land. Ebenezer Tucker was the first teacher, and notable attendees included Hiram Revels, the first black U.S. Senator, and James S. Hinton, the first black elected to the Indiana House of Representatives. In 1860 a two-story brick structure was built. The school was a noted Underground Railroad stop.

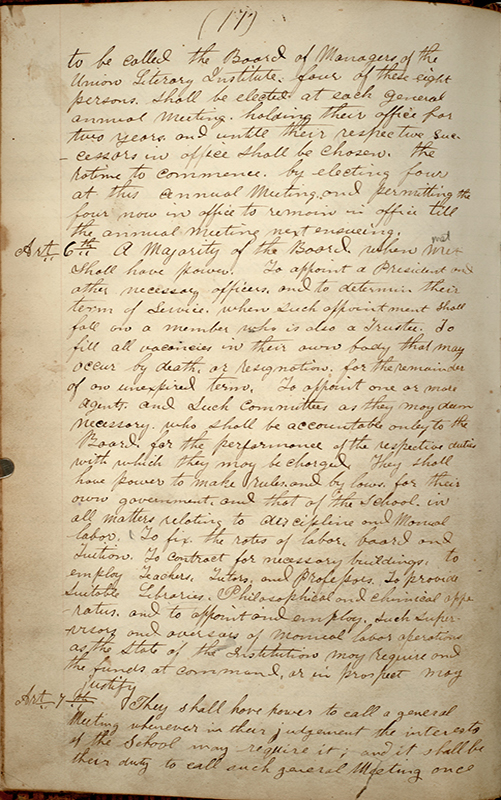

Union Literary Institute Constitution from the Board of Managers’ Secretary Book. BV1972_016-018, Indiana Historical Society.

On the Safest Route.

James and Rachel Sillivan cabin, Pennville (formerly Camden), Indiana, 2014

Several documents from the mid-1800s to the present indicate that Eliza Harris stayed at this location during her flight northward. Her crossing of the Ohio River would become one of the best known escapes due to her representation in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

A.S. Seer Print. Uncle Tom's cabin. , 1882. [N.Y.: A.S. Seer's Print]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington D.C.

Walk Along the Ridge.

Between the Maumee and St. Joseph Rivers, Braun-Leslie House, Fort Wayne, Indiana, 2014

Wayne County had many contributors to the Underground Railroad effort. Apparently by the 1850s Wayne County conductors and agents formed a Society of Underground Railroad workers, with a membership pledge and code. From Richmond, but mainly from Newport, conductors took enslaved blacks through Randolph and Jay counties to points east and west. In the east, splinter lines ran through Winchester, Marion, and Bluffton to Fort Wayne, then to Toledo, Ohio, and on to Canada. An alternative route was through Winchester, Marion, the Wabash-Huntington area, and Logansport. Addison Coffin, a transporter on the "line," wrote in 1844, "The Wabash line was in good running order and passengers very frequent." [Underground Railroad pledge with signature of J. Pease, Thomas Marshall Collection, Indiana Historical Society Library and Addison Coffin, Life and Travels of Addison Coffin (Cleveland, 1897), 88-89]

“Liberty to the fugitive captive and the oppressed over all the earth, both male and female of all colors.”

Sylvia and Captain John Lowry boldly invited freedom seekers to their home via a large board sign that was above the gate to their yard. It was painted with two figures, one white and the other black, holding a scroll between them. Their daughter, Mary E., described the sign: “The figure at the right is a female form, with heavy chain in the left hand, but broken are the links. In her right hand she holds the balances. To the left, and in the act of rising, is the figure of a man of darker hue … but, clad in freeman’s garb; while around one wrist is clasped the other end of slavery’s chain, with many missing links, and to his sister he looks up for help and perfect freedom, their faces all aglow with triumph, and just below appears this motto: ‘liberty to the fugitive captive and the oppressed over all the earth, both male and female of all colors.’” Carol E. Mull, The Underground Railroad in Michigan (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Publishers, 2010), 94.

By the 1850's there were six 'firmly rooted' black communities in Ontario, Canada. These communities served as havens for enslaved blacks prior to the Civil War.

1. Central Ontario (London, Queen's Bush, Brantford, Wilberforce)

2. Chatham (Dawn, Elgin)

3. Detroit Frontier (Amherstburgh, Sandwich, Windsor)

4. Niagara Peninsula (St. Catharine's, Niagara Falls, Newark, Fort Erie)

5. Northern Simcoe & Grey Counties (Oro, Collingwood, Owen Sound)

6. Urban Centers on Lake Ontario (Hamilton, Toronto)

Buxton (Elgin) Settlement 1849, now the Buxton National Historic Site & Museum- The Elgin Settlement, also known as Buxton, was one of four organized black settlements to be developed in Canada. The black population of Canada West and Chatham was already high due to the area's proximity to the United States. The land was purchased by the Elgin Association through the Presbyterian Synod for creating a settlement. The land lay twelve miles south of Chatham. The Reverend William King believed that blacks could function successfully in a working society if given the same educational opportunities as white children. "Blacks are intellectually capable of absorbing classical and abstract matters.” Being a reverend and teacher, the building of a school and church in the settlement was a necessity to him. The settlement also was home to the logging industry. George Brown, who later became one of the Fathers of Confederation, was a supporter of William King and helped build the settlement.

Emancipation Proclamation broadside, 1864. The Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

![[top] Manifest of a slave ship sailing from Richmond, Virginia, to New Orleans, October 18, 1840. African American Resource Center, New Orleans Public Library.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ab0037d5b409b60dd6390bb/1524758206520-5C0IZXEVLXLTVF2EUOQ1/SlaveShipManifest_1.jpg)

![[bottom]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ab0037d5b409b60dd6390bb/1524758368215-XDSCJ5NAM973RV5F3CPF/SlaveShipManifest_2.jpg)

![A.S. Seer Print. Uncle Tom's cabin. , 1882. [N.Y.: A.S. Seer's Print]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington D.C.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ab0037d5b409b60dd6390bb/1524786399391-0SKQ7VIH3W2MIPECKCEB/UncleTom%27sCabin.jpg)